In this second installment of the “Making of an Activist” series, the author explains the circumstances surrounding his resignation from the United Nations Special Commission, and the roots of his ongoing clash with the US government regarding US policy in Iraq and the Middle East.

In the beginning, there was a letter…

My resignation from UNSCOM was a long time in the making. For about a year prior to my departure, it had become apparent that UNSCOM was fighting a battle on two fronts – one against the Iraqis, who repeatedly confronted UNSCOM inspectors in their searches for hidden weapons, and the other against the United States, which repeatedly interfered with UNSCOM inspections to avoid such confrontation.

I had first thought about resigning in February 1998 when, together with the Deputy Director of UNSCOM, a U.S. State Department official named Charles Duelfer, I lambasted the decision by then-Secretary General of the United Nations, Kofi Annan, to allow the Iraqis to place severe limits on the scope and conduct of the very kind of inspections I had been charged to lead.

Duelfer was as equally frustrated as I was and, indeed, it was he who first mentioned the prospects of a resignation in protest. He handed me a copy of a draft resignation letter he was working on at the time, but which he never submitted. “Career suicide,” he said at the time. “Nothing will change, and I’ll be dragged across the coals and thrown to the wolves.” In retrospect, those were prophetic words, except it was me who ended up turning in the letter and subsequently paying the price.

I began active preparations for my own resignation in June 1998, after the US government placed even more constraints on my role as an inspector. I was pushing for a new campaign of inspections in Iraq which targeted the mechanism used by Iraq to conceal prohibited items and activities from the inspectors (the so-called “concealment mechanism”). This list of targets included several associated with the Iraqi presidency.

Scott will discuss this article and answer audience questions on Episode 58 of Ask the Inspector.

Charles Duelfer had encouraged me to press the Executive Chairman of UNSCOM, an Australian diplomat named Richard Butler, hard on this point, noting that U.S. intelligence believed Tariq Aziz and Kofi Annan had entered into an unwritten agreement that no so-called “presidential site inspections” would be carried out after the end of June 1998. American communication intercepts between Baghdad and New York proved that this was the Iraqi position; what wasn’t certain was where the Secretary-General stood. Duelfer wanted to find out.

I was more concerned about the legitimate arms control aspects of such an inspection, but given the fact that Saddam Hussein’s influential Presidential Secretary, Abid Hamid Mahmoud, played a critical role in coordinating the overall Iraqi concealment mechanism regarding weapons of mass destruction, finding an excuse to inspect presidential sites was not a problem.

My plan called for inspections of Abid’s offices, as well as the headquarters of the SSO and an office within Saddam’s Republican Palace in downtown Baghdad responsible for funding illicit covert procurement activities associated with ballistic missiles. Also included was the Ba’ath Party suspected missile component hide site in the downtown Baghdad suburb of Aadhamiyyah that had been provided by the British SIS a few days before.

Butler was concerned about how the Americans would react to such a target list. “This has all the makings of a confrontation,” he said. I had already briefed my contacts at the State Department (in the Special Commission Support Office, or SCSO) and the CIA (in the Non-Proliferation Center, or NPC) about the plan and its intended targets, and Duelfer had done the same with Bruce Reidel, who by this time had left the CIA for the National Security Council (NSC). Reidel seemed satisfied that the targets were legitimate, and the timing was right. Duelfer passed this on to Butler, who seemed satisfied. “Go to London,” he instructed me, “and sound out the British. We’ll need them onboard as well.”

As soon as I landed in London I contacted Susan Roome, the head of Operation Rockingham, the office within the Defense Intelligence Service (DIS) that handled UNSCOM liaison on behalf of the British. Susan told me we would be meeting at the office of Dr. Amanda Wedge, who headed up the Non-Proliferation Department in the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, or FCO.

It was a short walk from the Old War Office, where Rockingham had its offices, to the FCO building. Upon arrival at the FCO, I briefed Amanda and Susan on the proposed inspection concept. Amanda took the briefing in stride. “Derek Plumbley (the Chief of the Middle East Department of the FCO) has been saying that something like this is needed, so I think the timing is right. We will look at the details and get back to you on your way back to New York.”

The London trip was the first leg of a larger trip that took me to Israel and the Netherlands, where I had meetings with the respective intelligence services of those two nations to refine information about the targets we had selected for the inspection. A week later I was back in Amanda’s office. “Your proposal has received considerable attention here at the FCO,” Amanda said. “I think Derek Plumbley will be traveling to the United States soon for consultations with Richard Butler that should clarify the situation.”

“When will this be?” I asked.

“Sometime in the second week of July.”

“Do you know how Derek is going to weigh in on this?”

Amanda shrugged her shoulders. “As we have said, it is a promising concept, but one that requires some diplomatic preparation. I think Mr. Plumbley’s visit should be along those lines.”

Shortly after my return to the UN headquarters in New York, I flew down to Washington, DC to meet with my contacts at both the State Department and CIA about the inspection; everyone was enthusiastic and seemed ready to support the mission. All systems seemed to be primed for an inspection. I had one last final briefing with Richard and Duelfer in a booth in the UN cafeteria. Everything went smooth, but on Duelfer’s suggestion, I held off on submitting the inspection site notification documents for signature pending Butler’s upcoming meetings with the British and Americans.

Richard Butler had scheduled a pair of meetings for July 15, a mere three days before I was scheduled to fly out to Bahrain to join my team, which was already assembling and training for an inspection scheduled to begin on July 20. The first was at the United Kingdom mission, where he would speak with Derek Plumbley, and the other at the US Mission, where Peter Burleigh, the Deputy Ambassador, was waiting. Given the tenor of my meetings in London and Washington, DC, I expected a positive outcome.

I was to be disappointed. According to Butler, and contrary to what I had been led to believe, both the US and UK were balking at any inspection involving presidential sites; such inspections were deemed to be too confrontational and as such unsupportable given the current political climate within the Security Council, where Russia and France were becoming increasingly critical of what they viewed as an endless cycle of inconclusive inspection-driven crises that seemed designed only to extend economic sanctions levied against Iraq into perpetuity.

My frustration and anger at what had happened was such that I almost resigned at that time. I wrote a scathing memorandum to Butler, basically telling him to grow a backbone. (My words were actually more diplomatic, since I was assisted in drafting it by the British SIS New York liaison, who was as confused and frustrated as I was by the position taken by his government, especially given the fact that it was British intelligence that was driving a good part of the inspection in question.) If Butler did not respond to my recommendation, then I was out the door.

As it was, the memorandum bought me a month’s respite. Butler told me that the issue was “timing” and not the inspection per se. He was due to travel to Baghdad in early August for high-level talks with the Iraqis. I was instructed to accompany him, and have a new team assembled and ready to carry out inspections of all the targets originally scheduled for July once his meetings wrapped up on August 6.

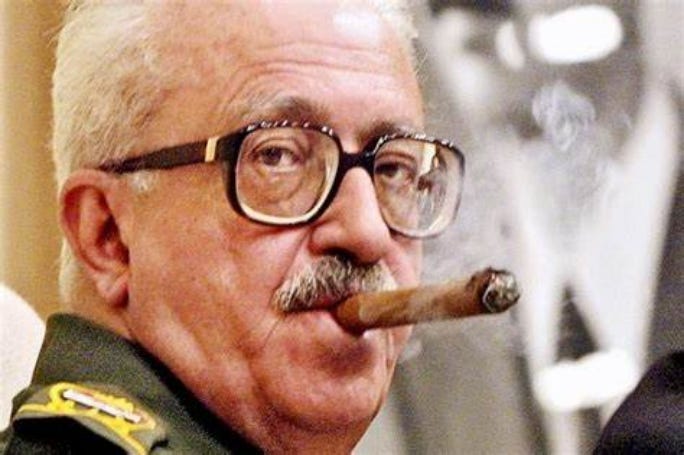

We arrived in Baghdad on August 3. By the close of business that day Iraq had put Butler on notice it would no longer cooperate with either him or any UNSCOM inspection of “discovery,” as intrusive inspections of the sort I was prepared to undertake were known. As Butler himself later acknowledged, the impasse reached on August 3 was one of implication. Tariq Aziz, the Iraqi Deputy Prime Minister, had terminated the talks that were taking place between himself and the Chairman (“Further discussion is useless,” the Iraqi Deputy Prime Minister told Butler.) Tariq Aziz did say, during this meeting, that Iraq would no longer cooperate with UNSCOM “disarmament inspections,” but this was, at the time it was made, more rhetoric than official policy (indeed, UNSCOM monitoring inspectors were able to continue their work until October 31, 1998, when Iraq stopped all cooperation with UNSCOM).

In a meeting between myself, Butler and Charles Duelfer later that evening, held in a special room used to make secure phone calls back to New York, I made just that point—all we had from Iraq was a verbal statement made in the heat of the moment. We needed to test what exactly Iraq meant by “no cooperation.” Was it merely a personal issue, between Tariq Aziz and Butler? Or was this a complete rejection of the commitments made by Iraq to Secretary General Kofi Annan back in February 1998? The only way to find out for sure would be to go forward with the planned inspections. Butler agreed and ordered me to remain in Baghdad and prepare to start the inspection on August 5 while he flew to Bahrain, and then to New York, to confer with the Security Council.

Butler flew out the next morning, August 4, seemingly ready to confront the Iraqis. But the next day I got a call from the Executive Chairman. He told me he had just spoken with Madeleine Albright, the US Secretary of State, who asked him to delay the inspection. I was put in a holding pattern until August 10, but even this date proved illusory. On August 7 Richard called me again and informed me that the US was pulling the plug on the inspection. I was ordered home.

This proved to be my breaking point. As soon as I got back to New York, I contacted Matt Lifflander, whose son, Justin, had worked with me back in the late 1980’s as a member of a team monitoring Soviet missile production at a factory outside the city of Votkinsk, in the foothills of the Ural Mountains as part of the Intermediate Nuclear Forces Treaty between the United States and the Soviet Union. Matt was a corporate lawyer who had worked for Senator “Scoop” Jackson in the 1970’s, and since that time had taken an active interest in national security affairs. He and I regularly met for lunch at the University Club in midtown Manhattan, where he grilled me for insights into the colorful world of UN inspections in Iraq. Matt was a friend, and discreet, and I was only too willing to meet with him and his business partners. It was at such a lunch, on May 28, 1998, that I first dropped the news that I was fed up with the situation at UNSCOM and was considering walking away.

“You mean resign,” Matt said.

“What’s the difference?” I asked.

“Simply walking away accomplishes nothing,” Matt replied. “A resignation, properly executed, can change the world.”

Resigning from a job such as the one I had in UNSCOM wasn’t an easy decision to make. I had been involved in the Iraq inspection business for almost seven years, and deeply believed in the work I and the other inspectors were doing. There was a narcotic-like quality to the life of a front-line weapons inspector, filled as it was with enough international intrigue to fill a John Le Carré novel (or two).

I had become accustomed to traveling around the world in search of intelligence that could be turned into inspections that took me and my fellow inspectors into the very heart of the regime of Iraq’s president, Saddam Hussein. Although we had, for the most part, operated outside the lens of the media, our work had not, and there were at least a half-dozen Security Council resolutions which threatened to take Iraq to the brink of war over its refusal to cooperate with teams I was either leading or involved in.

To transition from staring down the barrel of an AK-47 in Baghdad to tranquil domesticity in the suburbs of New York City was no easy thing. To do so without a plan on how one was going to pay the bills once the paychecks stop coming in was insane. When I again raised the issue of the possibility of my resigning, this time in mid-July, following the cancellation of a planned inspection at the behest of the U.S. and British governments, Matt was supportive, and helped me shape a plan of action. “You’ll need a media strategy,” Matt advised. “Otherwise, you will submit your letter, your bosses will remain silent, and the world will never know. And you and your family will starve.” Those words were sobering. “You will also need one hell of a resignation letter, one that can capture the imagination and motivate the kind of change you want to occur because of your action.”

I started drafting a letter the next day. I held off on submitting it when Richard Butler acquiesced to my insistence that we push forward with an aggressive, intelligence-based inspection in Iraq in early August. However, when this inspection, too, was canceled, the die was cast. I told Matt I was serious about resigning, and he started preparing for the consequences of that action.

When it came to public relations, I was next to useless. I was an inspector, not a spokesperson. My job was to stay out of the public eye, not actively engage it, something I had been quite good at. My resignation would be subjected to a great deal of scrutiny. It would be important not only to tell the whole truth, but also carefully pick those to whom I wanted to share the truth. Matt had some contacts in the media world he was willing to reach out to for advice and assistance and asked me if I had any of my own. As it turned out, I did.

More than a decade after my resignation, Charles Duelfer lambasted the impact on the work of UNSCOM and the Clinton administration’s Iraq policy on a series of Washington Post articles that appeared to be, according to Duelfer, “a coincidence of interests by a new young Post reporter who fortuitously inherited the UNSCOM beat and Ritter as a source just when Ritter was bursting with tales to tell.”

It was a strange thing for Duelfer to say, seeing as it was he who had introduced me to Barton Gellman, the Washington Post reporter in question, and actively encouraged and facilitated our cooperation in the days and weeks leading up to my resignation.

It had started as a simple “insurance policy” taken out in January 1998, when I had just been ordered out of Baghdad by Richard Butler. For a week, the Iraqis had been refusing to cooperate with the inspection team I had been leading, and Butler finally pulled the plug on our mission, ordering me to return to New York after stopping off in Bahrain, where I was to brief him on the details of the confrontation and my suggestions on how to resolve it. Butler was on his way to Baghdad to forestall yet another crisis between Iraq and the UN Security Council.

I had just left Butler’s suite in the Bahrain hotel he was staying at and ran into Duelfer as he made his way down the hall for his own meeting with the boss. “How’s it going in there?” Duelfer asked, gesturing toward Butler’s room.

“Not too bad. It’s not Munich—yet,” I replied, referring to the historical sell-out of Czechoslovakia to Adolf Hitler by the British Prime Minister, Chamberlain, in 1939. I gave Duelfer a rundown on the meeting, and then mumbled something about having a flight to catch. Duelfer suddenly got very serious.

“Look, Scott,” he said, “it’s insane back there. You have no idea. Be careful.”

I assumed that “there” meant New York, and that Duelfer was referring to the intense media interest that had erupted around the inspection in general and me in particular, culminating in an above-the-fold color photograph of myself on the cover of the New York Times. The UNSCOM offices in New York and Bahrain had been swamped with calls from the media, wanting to know when I would be returning. I laughed and explained that was why I was flying out now. “I’m taking an earlier flight. The camera crews will be waiting for the wrong plane.”

Duelfer shook his head. “No, no. You don’t understand. It’s not the media...Washington has gone crazy.”

I still didn’t comprehend. “About what?”

“You,” Duelfer replied. “I can’t get into it now but be careful.”

“Careful about what?” I shot back. “I’m not clear on what you’re saying.”

Duelfer reached inside his coat pocket and took out a business card and handed it to me. I examined it, noting the name and phone number of R. Jeffrey Smith, a well-known journalist from the Washington Post.

“Listen,” he said, “if things get too crazy, call this guy. He’s good, knows the basics of the story, and can serve as your insurance policy.”

I was absolutely dumbfounded. I had no idea what Duelfer was talking about and said so.

Duelfer was almost embarrassed. “Scott, I can’t talk about it. Please understand that.” He paused. “Did Butler say anything to you?”

I shook my head no.

Duelfer appeared to be groping for the right words. He was clearly uncomfortable. “Look, you know when we needed ‘Kurtz’ pulled out, and Butler was called over to the US Mission and briefed by Richardson?” “Richardson” was Bill Richardson, the amiable US Ambassador to the United Nations.

I blinked at Duelfer, my eyes narrowing as I tried to make sense of what Duelfer was trying to say. Duelfer’s reference to ‘Kurtz’ and the US intervention only confused me more. ‘Kurtz’ was an American deputy of the in-country concealment inspection team I controlled, a man of tremendous experience who was brought in to the team for the purpose of providing operational planning and leadership.

‘Kurtz’, of course, was not his real name, but a label put on this extraordinary individual by Duelfer. With his shaved head, walrus mustache and weathered face, our man was a combination of Robert Duvall’s Colonel Killgore and Marlon Brando’s Colonel Kurtz in the movie “Apocalypse Now.” With a wide-brim Stetson, cowboy boots and an ever-present wad of chewing tobacco stuck in his cheek, ‘Kurtz’ looked every bit the part.

‘Kurtz’ was picked for this job in part because his background, which was embedded in the world of covert special operations. His most recent assignment prior to coming on board at UNSCOM was preparing diplomats for E&E—escape and evasion—from hostile situations. When I interviewed ‘Kurtz’ for the position, I figured that such training might be ideal for situations the concealment team might find themselves in.

But ‘Kurtz’s’ background had been his undoing. He was, so to speak, too “black,” or covert, for his own good. Even though he was performing wonderfully in Iraq, his managers in Washington began to panic when the situation in Baghdad began to deteriorate in October 1997. A decision was taken to pull ‘Kurtz’ out of Iraq. It was bitter irony—the one man who was best-equipped to deal with a hostage situation, to keep not only himself but other, less fully-trained personnel alive and well, was being withdrawn in haste out of fear of his being taken hostage.

Once ‘Kurtz’ was assigned to UNSCOM, he was technically our property for the duration of the assignment, and the US could not just simply “snap” its fingers and bring him home, hence the summons of Richard Butler to the US Mission. Bill Richardson met with Butler and gave him a canned speech. “One of the personnel provided to you [‘Kurtz’] is a bit too exposed by the current situation, and we feel that it would be best for us all if he were withdrawn at this time.” Nothing more was said, but Butler fully understood. “Hell, the man’s CIA,” he said to me after his meeting with Richardson. “The Americans want him out.”

I still couldn’t see where Duelfer was going with this analogy. “What do I have to do with ‘Kurtz’?” I asked.

Duelfer laughed. “You were ‘Kurtzed,’” Duelfer said. “The reason why you and your team were pulled out early is because the US got cold feet.”

“‘Kurtzed’? Why?” I asked. “I don’t work for the CIA. What’s the worry?”

But now I was thinking back to the look in Butler’s eye back in the suite as I shook his hand goodbye. Since my first meeting with Richard Butler, I had been laboring to win over his trust and confidence. I was running the most sensitive operations in UNSCOM, and Butler was therefore convinced that I was somehow affiliated with the CIA. I had worked hard to prove to Butler that I was his asset, and that I reported to no one else. I felt I had made great progress in this effort, and by January 1998 could walk into Richard Butler’s office confident in having his full trust that I worked for him and him alone. If I had, as Duelfer said, been ‘Kurtzed’, then all that trust was out the window. To Butler, I would be just another CIA agent, never to be fully trusted again.

“That was a pretty stupid thing to do,” I said. “What were they worried about? The media coverage?” I had, after all, appeared on the cover of the New York Times, never a good thing if one wanted to maintain a degree of anonymity.

Duelfer looked at me in a manner which reflected that I was still not getting it. “No, Scott,” he said patiently. “Not the media coverage. You. They were worried about you.” Duelfer was getting antsy. “Listen. I can’t talk about this.”

But he did.

“One minute Sandy Berger [the national security advisor] is jumping around the NSC, backing your mission 100 percent, telling everyone ‘Let’s send in “Darth Ritter,”’ like it’s a big game.” Duelfer was referring to a nick-name first put on me by David Welch, a senior State Department official who helped manage UNSCOM-Iraq policy, back in December 1997, during an earlier confrontation between UNSCOM and Iraq.

“Then,” Duelfer continued, “the FBI goes to Berger and says, ‘Look, your poster-boy may not be all that you think he is. We think he’s taking his orders from the Israelis, and Berger panics. That was the end of the inspection.” Duelfer paused. “The next thing you know, you’re being ‘Kurtzed.’”

My head was spinning. I had, since October 1994, overseen a very sensitive liaison with Israel’s intelligence services for the purpose of collecting information of high quality that could help UNSCOM inspections in Iraq. While the US government had, on occasion, expressed concerns over the nature of this liaison, they continued to support it, including providing sensitive aerial photographs that would be examined by Israeli imagery analysts for use in developing inspection targets.

“What the hell is going on?” I finally managed to say. “Working for the Israelis? Everything I do over there is pre-approved by you, Butler and the CIA.”

Duelfer was clearly uncomfortable. “I can’t talk about it—I’ve probably already said too much already. I told you—Washington has gone insane. If things get too crazy,” Duelfer continued, pointing to the business card in my hand, “Don’t hesitate to call that number. I can’t tell you what to say, but it could be your best line of defense.”

I never did “play” the Jeff Smith card. On occasion Duelfer would call me up to his office to provide a background briefing for Mr. Smith on an article he was working on. My input was limited to making sure the dates and facts surrounding a specific chronology were correct, nothing more. In all cases, the contact with Mr. Smith had been originated by Duelfer, who was pushing one agenda or another—usually at the behest of Washington, DC. But sometimes Duelfer acted on his own volition, which was the case when, on August 12, a few days after my return from Baghdad following the termination of my inspection, my phone rang at my desk. “Come on up,” he said. “I have someone I’d like you to meet.”

I did so, and there, seated on a couch Duelfer kept in his office, was a young man with an unshaven face and the scruffy clothes of a beat reporter. “This is Bart Gellman,” Duelfer said. “He is taking over from Jeff Smith at the Washington Post.” I shook Gellman’s hand, and sat down in a chair next to a coffee table placed in front of Duelfer’s desk. It turned out that Duelfer had been speaking at great length with Gellman about the Butler-Albright connection, and the pair of telephone calls which triggered my team being pulled from Iraq.

I wasn’t shocked that Duelfer had decided to go to the press about Butler’s reversal on the inspection, and the role played by Secretary of State Albright in prompting it. There were indications that the meeting with Gellman was not the first one Duelfer had carried out about this matter. On August 10, three days after my conversation with Richard Butler, I was ordered home, and while I was still in transit back to New York, a scathing article appeared in The Times of London. “The United States,” the reporter for The Times, James Bone, wrote, “is so eager to avoid a new military confrontation with Iraq that it has blocked more United Nations weapons inspections this year than Baghdad.” Bone went on to note that “Madeleine Albright, the Secretary of State, is said to have intervened personally to urge restraint in a recent telephone call to Richard Butler, the UNSCOM chairman.”

I was struck by two aspects of this reporting. First was how timely (and accurate) it seemed to be. While the article had come out on August 10, the reporting for it took place on August 9, only two days after my conversation with Butler ordering me home. To my knowledge, there were only three people within UNSCOM who were aware of Butler’s conversations with Madeleine Albright at that time—Butler, myself and Duelfer. I hadn’t spoken to any reporters about Butler’s decision to cancel the inspection, let alone his conversations with Albright. I couldn’t imagine Butler willingly exposing his subservience to the Americans in this fashion.

This left Duelfer.

The second aspect of the article by James Bones dealt with the language he used. Duelfer had spent some time on the phone with me, both in Baghdad and Bahrain, trying to sooth my ruffled feathers over the canceled inspection and, based upon what he told me at the time, he shared my displeasure over the pressure brought to bear on Butler by Albright. Duelfer even went so far as to joke that “Madeleine Albright has blocked more inspections than Saddam Hussein” (a phrase Duelfer has acknowledged saying on several occasions.)

It was the similarity between Duelfer’s quip and James Bone’s anonymously attributed line about United States blocking more inspections than Baghdad that left me with no doubt that Duelfer, given his previous record of speaking on background to journalists when the mood struck him, was the source of Bone’s reporting. Now it seemed Duelfer wanted to continue this trend with Gellman. Gellman needed some corroboration for the information Duelfer had already shared, something that, given my mood, I was only too happy to provide. Afterwards Gellman handed me his card, which I tucked away in my wallet with little thought.

The next morning, Gellman’s article ran on the front page of the Washington Post. It accurately reported the facts of the aborted inspection, noting that I was in Baghdad with a “team of specialists” prepared “to mount ‘challenge inspections’ at two sites where intelligence leads suggested they could uncover forbidden weapons components and documents describing Iraqi efforts to conceal them.”

Gellman then dropped the hammer. “On Aug. 4 Butler notified the U.S. government that he had authorized Ritter’s team to conduct the raids on Aug. 6. That same day he got word that Albright wanted to speak to him and traveled to the U.S. Embassy in Bahrain for a secure discussion. Albright argued, according to knowledgeable accounts, that it would be a big mistake to proceed because the political stage had not been set in the Security Council.” Gellman went on to report that “After a second high-level caution from Washington last Friday [August 7], Butler canceled the special inspection and ordered his team to leave Baghdad. The disclosure was made yesterday by officials who regarded the abandoned leads as the most promising in years and objected to what they described as the American role in squelching them.”

The Washington Post article proved to be a bombshell. I almost felt bad for Richard Butler during the Friday morning staff meeting, when the article was discussed. He had to know that the source of the revelations contained in Gellman’s article were seated in the room with him. He knew that both Duelfer and I knew the truth about the pressure he had been placed under by Albright, yet Butler continued to stick to the story that he had told Gellman—while he coordinated with many nations about matters pertaining to policy regarding inspections, he and he alone made the operational decisions concerning inspections. Butler remained silent on the specific issue of whether Albright had urged him to cancel my inspection.

The Secretary of State, in a press conference convened on August 14, likewise denied ordering Butler to cancel any inspections. “We have conversations,” she said regarding Butler. “I’m not going to get into my conversations. I do not—let me make this perfectly clear—I do not tell Chairman Butler what to do.”

But these responses rang hollow in the face of the specificity of Gellman’s reporting, so Albright took the extraordinary step of penning an op-ed to the New York Times, which ran on Monday, August 17, 1998, to respond more fully to the accusations of US interference in the work of UNSCOM. In her op-ed, Albright acknowledged that UNSCOM had planned to conduct “some particularly intrusive inspections, which we supported.”

This was true enough. However, once Iraq suspended its cooperation with the inspectors, Albright wrote, the Americans had second thoughts, assessing that Iraq had overplayed its hand. “It was in that context,” Albright noted, “that I consulted with Mr. Butler, who came to his own conclusion that it was wiser to keep the focus on Iraq’s open defiance of the Security Council,” adding further that the inspections “would have been blocked anyway” and “some in the Security Council would have muddied the waters by claiming that UNSCOM had provoked Iraq.”

Richard Butler’s subservience to Washington, DC was on display for all the UNSCOM staff to see, and his unwillingness to meaningfully address it in the aftermath of the Washington Post article helped seal my decision to resign. “You will need to re-think the composition of your investigation team,” Richard told me early the next week, when I brought up paperwork for his signature, so we could bring in a new British expert as part of my concealment team. “Fewer Americans, fewer Brits.”

I added a Frenchman.

“And you’ll need to start reconsidering your role, as well,” he added. “You have too high of a profile. It makes the Americans nervous.”

I met with Matt Lifflander shortly afterwards to finalize my resignation.

Later, when Matt asked me if I had any media contacts, I knew exactly who to call. Bart Gellman indicated he was more than happy to write a story about my resignation for the Washington Post. I spoke with Gellman a few times by phone, and on August 24 he traveled to New York to meet with Matt and me to discuss the reasons behind my resignation. Matt provided Gellman with a draft copy of my proposed letter of resignation.

On August 25, the day before I submitted my letter of resignation, I met with Gellman in my office on the 30th floor of the UN Headquarters Building, where I provided him with documents that corroborated my case against the U.S. government and Richard Butler. Gellman left to make some calls based upon the information I had given him, but not before securing a promise from me to meet with him for lunch after I had submitted my resignation.

The next morning, August 26, I took the Metro North into Manhattan, and then walked to 30 Rockefeller Center, where Matt’s law firm had its offices. There Matt and I reviewed the press release he had prepared, together with the final draft of my resignation letter, making sure there were no errors. I had spent days crafting just the right words to capture my anger and frustration at what was going on with the betrayal of the inspection process by the United States. My wife, Marina, who possessed an editor’s eye (and whose grasp of the English language exceeded my own, despite her being a native of the Republic of Georgia), helped tone down the original drafts. “Too angry,” she said. “You’ll alienate the readers.” I then took the altered draft to Matt, who wielded his own pen to tighten the message. After days of work, we finally had something that fit the bill.

Matt was ready to send the press release to an impressive list of media contacts as soon as my resignation was final. I made my way from 30 Rockefeller to the UN Headquarters on foot, eschewing a cab, so the magnitude of what I was about to do could soak in. I had discussed the possibility of my resignation with Marina over the course of the past week. “It’s a job, Scott,” she had cautioned. “Not a cause. Who is going to pay the bills after you step down? How do you know anyone will care?”

We had twin five-year old daughters to take care of, not to mention Marina’s own parents, who lived with us ever since a civil war, and the accompanying ethnic cleansing, tore them from their home in Sukhumi, Georgia in 1993. “I’ll support you no matter what decision you make,” she said, “but unless you know how your resignation is going to play out, I wouldn’t do it. We need a paycheck to survive.”

Matt had spent a lot of time and effort lining up potential income streams for when I stopped being an inspector, including a book contract (I eventually signed with Simon & Schuster in December 1998), a speaker’s bureau (I contracted with Greater Talent Network in September 1998), and an on-air analyst (NBC News picked me up in November 1998).

But none of these deals existed as I walked the bustling streets of New York City that Wednesday morning. I hadn’t made up my mind until recently that I was going to go through with the resignation, and Matt couldn’t open discussions with anyone about my future until after the resignation was fact. I had no way of knowing if anything was going to reach fruition in terms of developing an income stream.

I also had no way of knowing if anyone would give a damn about my resignation. Would this be a one-day story, a flash-in-the pan that quickly fizzled out? If so, I was screwed, and so was my family. I was about to undertake one hell of a gamble. I hoped for the sake of my wife and twin daughters it paid off.

I called Duelfer when I got to my desk, and he came down to see me. “Well?” he asked. I handed him the letter, which he read carefully. “This is good stuff, Scott. Well written.” Much of the language was derived from our previous discussions, and as such familiar to Duelfer. “You’re going to piss a lot of people off. I almost wish I was the one submitting this—almost.” He laughed as he handed the letter back to me. “Are you sure you want to go through with this?”

“I’ve come too far to back down now,” I replied, sounding more certain than I felt.

“Well, I envy you your clarity. But do me a favor. Go over to the U.S. Mission and check in with Larry Sanchez before you give this to Butler. I gave Larry a heads up you might be resigning. He wants to talk to you about it before you submit the letter.”

“You mean talk me out of it.”

Duelfer laughed. “No. He’s on your side. But he works for the administration. They aren’t too happy.”

Larry Sanchez was the CIA’s liaison to the U.S. Mission to the United Nations. Before that he had headed up the International Organization’s desk at the CIA’s Non-Proliferation Center, or NPC, responsible for the UNSCOM account. Larry had been instrumental in bringing me back to the UN after I took a brief sojourn with the Marines in 1994-1995. We had worked closely on several sensitive issues, and Larry had always been a straight shooter. I owed him that much.

The U.S. Mission was located across the street from the visitor’s entrance to the UN Headquarters Building, so it was only a matter of minutes before I found myself being checked in by the security guard behind the first-floor desk and led to an elevator which took me up to an upper floor where the CIA kept its offices. Inside a secure vault, surrounded by desks strewn with highly classified documents and message traffic, Larry was waiting. We chatted for a bit about the ramifications of what I was about to do. “The fallout will be considerable,” he said. “You may end up killing off the inspections. Is that really the result you want?”

“They might as well be dead now,” I said. “Perhaps this will be what it takes to jump start them back into life.”

“Maybe.” Like Duelfer had said, Larry was sympathetic. He had been on the frontline, so to speak, of the CIA’s efforts supporting both me and the inspections I was involved in and was personally unhappy with the direction US policy was heading vis-à-vis UNSCOM. “They want to talk with you first. To see if they can change your mind.”

“They” was code for the faceless bureaucracy in Washington, DC from which nothing good had emerged concerning Iraq and inspections for such a long time. Larry had dialed a number on his STU-III, a black secure telephone used for classified talks, and handed me the handset. On the other end was David Welch, the State Department official who had once labeled me ‘Darth Ritter’. The conversation was short and to the point. The U.S. wanted me to stay. Their policy toward confrontational inspections had not changed. I couldn’t continue to work under such conditions. The resignation was going through.

I hung up with Welch, and Larry and I talked shop for a bit. Then he shook my hand. “Well, this is it. You’ll be radioactive from this point on. They are plenty mad at you. The gloves are going to come off, and the FBI is going to fuck you in the ass. But I guess you know that already.”

Larry’s comment took me back two months, to early June, when I was in the middle of a complex series of discussions with the Israelis, Dutch and British about a particularly sensitive operation involving Iraqi defectors and covert procurement activities being undertaken by Baghdad. I was headed to the Israeli Mission for a meeting with Naor Gilon, the First Secretary who served as my New York point of contact with Israeli intelligence. Larry was crossing First Avenue as I exited the main gate of the UN, and we bumped into each other, more by design than accident. He had his trademark smile in place as we exchanged pleasantries. “I’ve been in touch with the bureau [FBI], and it appears that they are ready to meet with you and discuss their concerns.”

I was pleased to hear this. I had been pushing for such a meeting ever since Duelfer told me of the FBI’s conversation with Sandy Berger back in January, after Butler had me pulled out of Baghdad. I had protested the FBI’s interest in my work for UNSCOM to both Butler and Duelfer once I got back from Iraq, and they had both interceded on my behalf with Bill Richardson and Sandy Berger, both of whom professed ignorance of the issue and a hesitancy to get involved in a “law enforcement” matter.

Only Larry had shown any courage in following through, and in the spring, he had called me over to his office in the U.S. Mission to show me a classified letter from the CIA’s legal counsel to the Justice Department which outlined my relationship with the CIA and noted that everything I did was done with the approval of the U.S. government. In any event, the CIA memo noted, I lacked security clearances, and since any information given to me by the U.S. government was, by definition, considered unclassified, I was not in any position to be violating any laws regarding the handling of classified material. I thought that this letter would be the end of the story, but Larry had come back to me with a request from the FBI to meet with me. “They’re still worried about your connection with Israel,” he said.

I had agreed, but then had heard nothing back from either Larry or the FBI for several months, until bumping into Larry on First Avenue. “Great,” I replied. “When will this take place?”

Larry looked embarrassed. “Soon, perhaps within the next forty-eight hours. I wouldn’t be surprised if they simply pulled you off the street and took you in.”

“You’ve got to be kidding me,” I said, incredulously. “Are they talking about arresting me?”

Larry shrugged. “Hey, you never know with these guys.” He looked behind us, up at the Tudor Towers which loomed over us across First Avenue. “Well, I think we’ve given them plenty of time to photograph us together. Where are you headed to now?”

I laughed out loud. “The Israeli Mission.”

Larry shared the joke. “That will throw the bureau for a loop. I better get going before they think I’m in on it with you, and I find myself handcuffed to a chair downtown.”

Larry smiled. I knew what he said to be true, but it was a bit disconcerting to hear it put so graphically. (The FBI never did pick me up for questioning, but neither did their interest in me diminish.)

Duelfer was waiting for me in the foyer of the main UNSCOM office suite on the 31st floor, where he and Richard Butler, plus senior staff, worked. We approached the desk of the Chairman’s Executive Secretary, Olivia Platon, and asked if we could see the Chairman. “He’s expecting you,” Olivia said. I had known her for almost seven years, a consummate professional and a friend. “Good luck,” she whispered. I guess the word had gotten around about what I was getting ready to do.

I handed Butler the letter. He read the words it contained quietly before putting it down on his desk. “You’re a man of principle, Scott,” he said, shaking my hand. “I wish you the best of luck, and hope that your actions will achieve the results you and I hope they will.” That was it. My tenure as an inspector was over.

“My team and I will be getting together over at the Helmsley Hotel for some drinks after work,” I said. “You’re welcome to join us.”

“I wouldn’t miss it for the world,” he replied.

Duelfer walked me out of the Chairman’s office. “Do you need to collect your things?” he asked. I shook my head. I had cleaned out my desk the night before, after my meeting with Bart Gellman. There was nothing left in the building for me.

“Do you have time for a quick bite to eat?” I thought about Bart Gellman, who had told me the night before that he wanted to meet at the Palm Two, a restaurant in mid-town Manhattan, once I had finalized my resignation. Gellman could wait, I thought. Duelfer had been a good boss who had backed me to the hilt over the years as I stressed the system with aggressive and controversial inspection concepts. If Duelfer wanted lunch, we’d eat lunch.

Lunch turned out to be something else. We headed north up First Avenue, before stopping at a restaurant I had never eaten at before. Waiting for us at a reserved table was an attractive brunette. Duelfer made the introduction. “This is Judith Miller. She’s a reporter for the New York Times. She’d like a shot at covering your resignation.”

Bart Gellman quickly crossed my mind. While we had never really hammered out the terms of our “arrangement,” I assumed that he wanted as exclusive a story as he could get. I already had given him access to a wealth of corroborating information, backed up by a treasure trove of documents. A single conversation over lunch with a reporter, even one as seemingly talented as Judith Miller, couldn’t compete with the access he had been given. For the second time in less than thirty minutes, Gellman took a back seat.

The meeting with Judith Miller proved to be short and sweet. Duelfer had already provided her with a copy of my resignation letter. She asked a series of questions, took copious notes, and then abruptly excused herself. “I’ve got some work to do if we’re going to get this to press by tomorrow,” she said.

Duelfer and I watched her walk away. “She’s a good one to have on your side,” he said. “She knows the right people, has access, and her stories get attention.” Obviously Duelfer had worked with her before.

“A good insurance policy,” I quipped.

“You’re going to need one.” Duelfer did not know about my meetings with Bart Gellman. He got up to leave. “I’ve got to go prepare for digging UNSCOM out from under the shit storm you’re about to unleash.” We shook hands, and parted company. I quickly headed over to the Palm Two, where Gellman was waiting.

The Palm Two is a pub/restaurant on Manhattan’s Second Avenue, close enough to the UN Headquarters to walk for lunch, but far enough away that one didn’t just stray into it. I needed a little privacy, given what was about to occur. Waiting for me in a booth in the corner were two men. One I recognized as Bart Gellman, the Washington Post reporter and erstwhile principle “insurance policy.”

He I expected.

Seated next to him was Jim Hoagland, a noted columnist for the Washington Post’s opinion page.

He I did not.

Gellman had worked his sources overnight and had some follow-up questions. Apparently, his initial outline had caught the interest of his editors, because Hoagland had flown up that morning to interview me as well. His column and Gellman’s front-page article would grace the pages of the next edition of the Washington Post. I could see some worry in Gellman’s face as he watched me walk up to where he and Hoagland sat. “Well, did you do it?” he asked. I understood his angst—you can’t have a story about a resignation unless the actual resignation letter was, in fact, submitted.

“Richard Butler accepted my letter without reservation,” I replied. “It’s a done deal.” I saw the relief flood into his eyes as I sat down at the booth. His story was safe. I spent the next hour or so fielding questions from the two men. When they were done, Gellman asked me what I planned on doing next. “I’m going drinking with my team,” I replied. “We’ve been through a lot together, and they deserve at least that much.”

But my day wasn’t done just yet. I made my way back to 30 Rockefeller Center, where Matt waited anxiously. “I’m no longer an inspector,” I told him.

“That’s OK,” he replied. “Now let’s turn you into a symbol.”

Matt and I took a cab to a non-descript building in midtown Manhattan and took an elevator up to a dimly lit floor where we found ourselves standing outside the office of short, pudgy old man with glasses, a bow tie, and a shock of silver hair. “This is Abe Rosenthal,” Matt said. “He used to be the editor at the New York Times, and now he writes an occasional column for their opinion page. He’s interested in your story.” For the third time that day I found myself sitting across from a journalist, explaining the whys and wherefores of my decision to resign from UNSCOM.

Matt parted with me after the interview. It had gone well enough, but Mr. Rosenthal had been non-committal as to whether he’d be writing anything. “We’ll see what happens,” Matt said in the elevator. “His voice is very influential, and he doesn’t lend it to just anyone.” He shook my hand. “Get a good night’s sleep. Tomorrow we’ll find out if this story has any traction or not.”

I waited for Marina outside the main entrance to the UN Headquarters where she worked as a tour guide. I still had my badge but felt ill at ease entering the grounds of an organization I had just resigned from. “Well,” she asked. “Are you unemployed?” She was only half joking. I was, I said. She gave me a hug and a kiss, and together we walked to the Helmsley Hotel. Some of our friends and colleagues were already there, waiting. More soon arrived including, much to our pleasant surprise, Richard Butler. We shared drinks and stories for hours, before breaking up.

The next day was a Thursday, and my former colleagues had work to do. Marina and I took the train home. In the morning, we took the train back into the city. Marina made her way to UN Headquarters Building. I made my way to 30 Rockefeller Center, where Matt waited. On my way I picked up copies of the New York Times and the Washington Post, seeking an answer to the question as to whether anyone cared about what I had done.

“Inspector Quits UN Team, Says Council Bowing to Defiant Iraq,” the Post proclaimed from its front page. Another headline read, “US Tried to Halt Several Searches.” Both stories were written by Barton Gellman. They were both significant articles, rich in detail. Gellman had obviously done his job.

I turned to the opinion page. There, Jim Hoagland’s column, “Ritter’s Resignation,” spoke of a “letter of resignation redolent with controlled rage and frustration.” Hoagland went on to predict that “Ritter’s resignation will resonate in Washington. Congressional committees will probe next month the administration’s failure since last winter’s war scare to provide effective diplomatic and military support for Ritter and other UN Special Commission inspectors.”

The headline of the New York Times was smaller, as was the article, but it still made the front page: “American Inspector on Iraq Quits, Accusing UN and US of Cave-In.” Judith Miller may not have had the head-start Gellman did, but she had acquitted herself well. But the real shocker came when I opened the paper to the opinion page. The answer as to what Abe Rosenthal had thought of our conversation was laid before me in black and white, in a column entitled “Scott Ritter’s Decision.”

“In seven years as a key UN inspector searching out Saddam Hussein’s concealed capabilities to make weapons of mass destruction,” Rosenthal wrote, “Scott Ritter had to call on all the physical courage in him. Then on Wednesday he summoned up all his moral and intellectual courage, and resigned. In his letter of resignation…he gave the world his reasons, with candor we have almost forgotten…letting the world know arms control in Iraq was an ‘illusion, more dangerous than no arms control at all.’”

Reading these words, a wave of relief swept over me. My gesture was neither futile nor empty, and my letter of resignation, magnified by the reporting of Barton Gellman and Judith Miller and enhanced with the advocacy of Jim Hoagland and Abe Rosenthal, had become, as Matt predicted, the centerpiece of a cause, the scope and scale of which I could scarcely imagine at the time.

Better than a Grisham novel , and great advice on impact resigning!

"Simply walking away accomplishes nothing,” Matt replied. “A resignation, properly executed, can change the world.

You’ll need a media strategy,” Matt advised. “Otherwise, you will submit your letter, your bosses will remain silent, and the world will never know. And you and your family will starve.” Those words were sobering. “You will also need one hell of a resignation letter, one that can capture the imagination and motivate the kind of change you want to occur because of your action.”

What cracks me up is my observations are based upon my first hand experience. If you disagree with me, that’s fine. But explain the basis of your disagreement—what first hand experience do you have. Book knowledge is fine, but it doesn’t trump being there.