“In 1981, an unidentified Soviet scientist approached an American journalist in Moscow and handed him a mysterious package. Sometime later the package found its way from the journalist to the CIA. The journalist asked for and received a pledge of secrecy from the agency…the package was an intelligence windfall. Analysts at the CIA’s Office of Scientific and Weapons Research examining the 250 pages contained in the package found data on the Soviet strategic weapons program that had until then been the subject of only the most speculative analysis. The level of detail and precision in the documentation could redraw American assessments of Soviet nuclear weapons development…the Soviet weapons experts inside the US intelligence community were unanimous: The information included in the package was simply too sensitive, too revealing, to be disinformation designed to confuse the West. The information was so good, in fact, that the anonymous volunteer held the promise of being one of the most highly prized sources the CIA might ever obtain on the Soviet nuclear target.”

If the above reads like a script pitch for The Russia House, a 1990 film adaptation of John le Carré's 1989 book of the same name, it is because the two narratives coincide. In The Russia House, a British publisher named Bartholomew “Barley” Scott-Blair, played by Sean Connery, becomes entangled with a young Soviet lady named Katya Orlova, played by Michelle Pfeiffer. Orlova had handed a “manuscript” prepared by a noted Soviet physicist to Nicky Landau, played by Nicholas Woodeson. Landau was supposed to hand the “manuscript” off to Barley, but instead turned it over to British intelligence, who determined the papers contained highly secret information about the Soviet Union’s strategic nuclear forces. The information was so sensitive that the British, together with the CIA, approached Barley to contact the Soviet physicist. The narrative then unfolds into your classic spy-versus-spy, man-meets-woman, adventure-love story that Hollywood is famous for.

The first narrative, however, doesn’t come from the fertile mind of le Carré or Hollywood, but from the annals of reality. The passage is from a book, The Main Enemy: The Inside Story of the CIA’s Final Showdown with the KGB, published in 2004. The co-author of The Main Enemy is Milton Beardon, the legendary CIA officer who served as the CIA’s Chief of Station in Pakistan from 1986 to 1989, where he managed the CIA’s covert war against the Soviet Union in Afghanistan. Beardon went on to head up the CIA’s Soviet/East European Division during the final years of the Soviet Union. Beardon’s co-author is James Risen, who at the time the book was published was a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist for The New York Times.

In The Main Enemy, Beardon and Risen offer up some insights into the murky connectivity between journalists and the CIA, as both pursue information inside the tightly controlled territory of the former Soviet Union. In doing so, they shed important light on the case of Nicholas Daniloff, the US News and World Report bureau chief arrested by the KGB in 1986 and subsequently charged with espionage, and the ongoing case of Evan Gershkovich, the Wall Street Journal journalist recently arrested by Russian authorities on similar charges. While it is too early in the Gershkovich case to draw meaningful parallels with the Daniloff affair, there are some similarities which, when examined from the perspective that all was not what it seemed with Daniloff’s arrest, may not bode well for Gershkovich going forward.

“I was Moscow bureau chief for US News & World Report,” Nicholas Daniloff recently wrote in an OpEd published in the Wall Street Journal, “on Aug. 30, 1986, when the KGB arrested me and falsely accused me of being a spy. I know,” Daniloff wrote, “what Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich and his family are going through.”

Scott Ritter will discuss this article and answer audience questions on Episode 61 of Ask the Inspector.

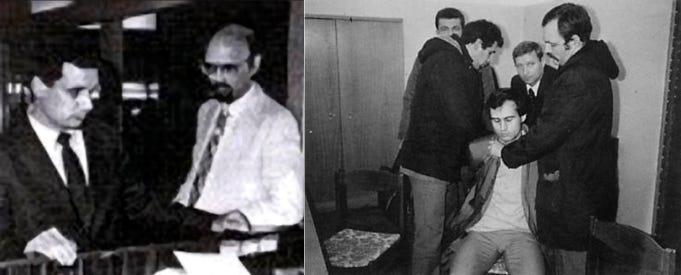

According to Daniloff, his travails began after, as he put it, “I met a friend, or so I thought, to say farewell in a park near my apartment. We exchanged parting gifts. A white van I had noticed earlier pulled up beside me. The door slid open abruptly and half a dozen men emerged.” Daniloff was arrested and taken to prison, where, in his words, “I was lined up and photographed outside the prison holding the plastic bag containing the gift my so-called friend had given me.”

That “so-called” friend was one Mikhail Anatolevich Luzin, better known as “Misha,” described by Daniloff as “a bright young man” in his mid-20s, and a well-known Soviet “fixer” who worked the hotels in the city of Frunze (present day Bishkek, the capitol of Kirghizia). Daniloff had first met “Misha” in 1982 and, according to Daniloff, the two met in a wooded lane in the Lenin Hills neighborhood of Moscow. Daniloff, whose five-year posting to Moscow was coming to an end, claims the meeting was simply two friends saying farewell to one another.

The Soviets tell a different story.

On August 29, 1986, Daniloff received a phone call from “Misha,” who informed the journalist that he was in possession of information Daniloff had previously expressed an interest in obtaining. According to statements made by “Misha” to Soviet authorities afterwards, Daniloff had asked him to gather information about restricted areas in the city of Frunze (a well-known transit point for Soviet forces heading in and out of Afghanistan), along with photographs of Soviet military equipment used in Afghanistan, data about military units being prepared to be dispatched to Afghanistan, and the contact information for Soviet soldiers demobilized after serving in Afghanistan.

“Misha,” it seems, had followed through on Daniloff’s requests.

At 11 am on the morning of August 30, Daniloff was waiting at the entrance of the Leninsky Propekt station of the Moscow Metro when “Misha” approached him. Soviet surveillance picked up the following conversation.

Daniloff: “Have you brough it?”

“Misha”: “Of course. Just as I promised.”

Daniloff: “Let’s go then.”

The two men then walked toward the Moskva River embankment, where they positioned themselves behind a large shrub intended to shield them from view. Daniloff handed “Misha” some books, and in turn “Misha” passed to Daniloff a package which was in Daniloff’s possession when Soviet authorities arrested him moments later.

In the package was a map of Afghanistan, marked “Secret,” with handwritten notes annotating Soviet troop dispositions, a hand-drawn diagram showing the location of Soviet military equipment in Afghanistan, and 26 photographs showing Soviet soldiers and equipment in Afghanistan.

This wasn’t the first time “Misha” had passed information of this nature to Daniloff. In the summer of 1985 Daniloff had received a package of similar material, including a map of Afghanistan marked “Secret,” which he had passed along to US News & World Report, which filed it away without making use of it. This repeated contact with a Soviet citizen for the purpose of collecting what amounts to state secrets led Soviet authorities to accuse Daniloff of trying to recruit “Misha” on behalf of the CIA.

This last action begs the question as to why the information from “Misha” was so important to a journalist who was literally days from completing his tour of duty? There was no chance of follow-up, no opportunity to develop the story further. This was a “farewell” meeting, according to Daniloff, so there was no effort to turn “Misha” over to Daniloff’s replacement. The information “Misha” had turned over seemed destined to be “filed” with the earlier packet of information, information no one would use, deemed not to possess any meaningful news worthiness.

This narrative makes no sense. Deciphering why, however, requires one to take a separate journalistic journey with Nicholas Daniloff, the roots of which can be traced back to the 250-page manuscript turned over to an unnamed US journalist in Moscow, who in turn passed it to the CIA.

Burton Gerber was the Chief of Station in Moscow when the manuscript came into the possession of the CIA. One of his top priorities was running a Soviet agent, Adolf Tolkachev, known in CIA circles as “the billion-dollar spy” for the money he saved the US by providing sensitive secrets about Soviet fight aircraft radar capabilities. Tolkachev had been a “volunteer,” someone who approached the CIA as opposed to having been groomed and recruited by the CIA.

Given the value associated with Tolkachev, Gerber was very keen on following through when it came to identifying the author of the 250-page manuscript detailing Soviet strategic missile capabilities. This was essential, given the fact that the author had deliberately left out critical pieces of information to make him valuable going forward. Gerber had coordinated closely with the CIA’s Soviet Branch Chief back in the CIAs Headquarters in Langley, analyzing the clues contained within the manuscript to form a profile of the potential author. But in the end, the CIA ran into a dead end, and the manuscript was filed away.

In December 1984 Nicholas Daniloff received a phone call from a man who identified himself as Father Roman Potemkin, an Orthodox priest. Father Roman claimed to want to meet with Daniloff to discuss political dissidents inside the Soviet Union. Daniloff spoke briefly with the Russian clergyman, before hanging up. Daniloff was concerned that Father Roman might be a “dangle” from the KGB, trying to get the American journalist to engage in politically sensitive reporting that could lead to his expulsion from the Soviet Union.

Daniloff thought nothing more of the call until the morning of January 24, 1985, when he found an unstamped envelope inside the mailbox hanging on the door to his office. The envelope was addressed to him. Inside was another envelope, addressed to Arthur Hartmann, the US Ambassador.

While Daniloff later claimed that he thought the envelope might be a setup by the KGB, what the erstwhile journalist did immediately afterward suggests otherwise—he and his wife immediately drove to the US Embassy, conducting (by his own admission) countersurveillance maneuvers designed to detect whether he was being followed.

Upon arrival at the US Embassy, the Daniloffs were waived in by a US Marine guard. One of the Marines assigned to the Moscow Embassy was a young sergeant named Clayton Lonetree. Lonetree was later arrested and charged with espionage for allowing the KGB after-hour access to the US Embassy grounds. Lonetree, who was subsequently found guilty at trial, had fallen victim to a “honey trap,” a young Soviet female employee of the Embassy who turned out to be working for the KGB. Following Lonetree’s arrest, the US Embassy fired all of the Soviet employees. However, at the time Daniloff arrived on January 24, 1985, the Embassy building was full of Soviet employees, all of whom were tasked with reporting what they observed back to the KGB.

At the Embassy, Daniloff met with Ray Benson, a veteran press and cultural affairs officer with significant experience in the Soviet Union. To any Soviet employee watching, this would be a normal meeting in keeping with Daniloff’s position as an accredited journalist. Inside Benson’s office, out of sight of any prying Soviet eyes, the two men opened the second envelope, only to find a third, addressed to William Casey, the CIA Director. The letter was handwritten, 6-7 pages long, and, according to Daniloff, contained multiple references to “rockets.” Daniloff left the letter with Benson, and departed the Embassy, believing, as he later contended, that he had washed his hands of this incident.

Benson passed the letter on to Murat Natirboff, an experienced CIA officer who took over as the Moscow Chief of Station from Burton Gerber in 1984. Natirboff in turn forwarded the letter to Gerber, who had left Moscow to head up the Soviet Branch at CIA Headquarters. Gerber believed that the Daniloff letter might be from the author of the original 250-page manuscript trying once again to make contact—to “volunteer” his services. After all, Tolkachev had to approach the CIA multiple times over the course of more than a year before the CIA agreed to begin running him as an agent. If the information contained in the 250-page manuscript could be confirmed as accurate, this new “volunteer” could potentially be even more valuable than “the billion-dollar spy.” But first they needed to know more about the man Daniloff believed had delivered the envelope to him—Father Roman. And to do that, the CIA needed to talk to Daniloff.

In early March, 1985, Daniloff was approached by Curt Kamman, the deputy chief of mission at the US Embassy. Kamman invited Daniloff to the Embassy, where he took Daniloff to a special sound-proof room used by the political staff. There, Daniloff met with the CIA Chief of Station, Murat Natirboff, who subsequently debriefed Daniloff about Father Roman. Daniloff was able to provide Natirboff a physical description of the priest, as well as a phone number that the priest had provided him back in December 1984. At the conclusion of the meeting Daniloff claims he told Natirboff that he wanted nothing further to do with the Father Roman affair.

Natirboff subsequently passed the phone number over to the National Security Agency, which in turn was able to match the number to a Moscow address.

The question now confronting the CIA was how best to proceed. In consultations with Gerber, Natirboff determined that the best approach would be for an experienced case officer to contact Father Roman directly. In mid-March, Natirboff, assisted by a case officer named Michael Sellers, worked with Gerber to carefully craft a letter for Father Roman that would be passed to him during the meeting. Once the language was agreed to, a second case officer, Paul Stombaugh, was selected to be the deliveryman.

On March 23, 1985, Stombaugh, a former FBI agent who was on his first assignment as a CIA case officer, made his way to a pay phone close to the address where Father Roman was said to live. Stombaugh placed a call, only to have a woman answer who claimed to be Father Roman’s mother. Stombaugh called back in an hour from another pay phone, and a man claiming to be Father Roman answered.

What happened next is a matter of much controversy. “I’m a friend of Nikolai,” Stombaugh told Father Roman, before declaring that he had received “the package” that had been delivered to Daniloff. In short, Stombaugh had outed himself as a CIA agent on an open line—this after violating protocol by calling back after someone other than the intended target had answered the phone.

Father Roman agreed to meet with Stombaugh, who went to the apartment listed as belonging to the phone number he called. There, Stombaugh handed a man fitting the description of Father Roman provided by Daniloff the letter crafted by Gerber, Natirboff, and Sellers earlier that month. The letter likewise noted that the CIA had received “your package from your journalist friend.”

Whether he wanted it or not, Daniloff had just been directly implicated by the CIA in its effort to recruit Father Roman.

The letter from the CIA to Father Roman had provided instructions for a meeting to take place on March 26. However, when Stombaugh showed up at the designated location, Father Roman was not there.

On April 5, Father Roman contacted Daniloff directly. The March 26 meeting with the CIA had been aborted, he said, because of surveillance, but he was ready to try and meet again. Six days later, on April 11, Daniloff approached Kamman at a reception at Spaso House, the US Ambassador’s residence in Moscow, and told him about the conversation with Father Roman. Kamman told Daniloff that someone would get back to him.

But on April 18 the Father Roman case took a strange turn. During a meeting between Michael Sellers and a KGB officer, Sergei Vorontsev, who appeared to be cooperating with the CIA, Voronstsev told Sellers that the KGB was aware of the contact with Father Roman. In short, Father Roman was not the person who sent either the original 250-page manuscript or the 6-7 page follow-on letter. When Strombaugh handed the CIA’s letter to Father Roman, the priest immediately took it to the KGB.

Later that month Daniloff was called back to the Embassy. In a one-on-one meeting with Nazirboff, Daniloff was told that Father Roman was under the control of the KGB, and that all further contact should be called off.

On June 9, Adolf Tolkachev was arrested by the KGB. He had been betrayed by a disgruntled CIA officer, Edward Lee Howard, who had undergone training for an assignment in Moscow and as such was knowledgeable about the identities of the agents he was being trained to handle. On June 13, Paul Stombaugh, while attempting to meet with a KGB double posing as Tolkachev, was arrested by the KGB and subsequently expelled from the Soviet Union.

In March 1986 Michael Sellers was on his way to meet with Sergei Vorontsev when he was arrested by the KGB. Vorontsev had been identified by another CIA officer, Aldrich Ames. Stombaugh and Sellers were two of five Moscow-based CIA officers caught in the line of duty by the KGB, and subsequently evicted from the Soviet Union, between June 1985 and July 1986. On August 30, 1986, Nicholas Daniloff was arrested after receiving a packet of classified information from “Misha.”

Three days later, Murat Natirboff left Moscow for Langley, his tour cut short because of the Daniloff arrest.

After Daniloff was arrested, the Soviets published details of the case they had assembled against him, including the interactions between Paul Stombaugh and Father Roman where Daniloff was specifically referred to. In an unprecedented move, the US government went public with the details of Daniloff’s interaction with the CIA regarding the Father Roman affair to blunt the impact of these revelations should Daniloff have gone to trial. In the end, Daniloff was released as part of a prisoner exchange involving a Soviet diplomat whom the FBI had arrested on espionage charges in the United States. President Reagan was getting ready to meet with Mikhail Gorbachev in Reykjavik, Iceland, and the Daniloff affair was making such a meeting politically difficult to pull off.

In a statement made after he was turned over to the custody of the US Embassy, Daniloff declared that “I have no official or secret relationship with any intelligence agency—everything that I have done in the U.S.S.R. has been on my personal initiative or on request of my magazine, U.S. News & World Report.”

The facts surrounding his arrest strongly suggest otherwise.

The Russians have yet to make public the details behind their decision to arrest Evan Gershkovich. The Daniloff case, however, provides a sobering precedent. Regardless of how Daniloff and the US government have tried to spin the circumstances surrounding his arrest, the fact is the Soviets were on extremely solid ground in charging him with espionage, because frankly speaking there is no other way to describe what Daniloff was doing.

Given the Russian propensity for building a solid case before acting, one can assume that the dossier the Russians have on Evan Gershkovich is as damning as the one they had assembled for Daniloff. The only difference this time is that there is no looming diplomatic summit which could engender a goodwill gesture on the part of the Russians. Evan Gershkovich is most likely condemned by his own actions to spend months if not years behind bars in a Russian prison. And, like Daniloff, he most likely has both himself and the CIA to blame.

Russia could score even more points than it has recently around the globe by offering to exchange Evan for Julian Assange. Fair minded people everywhere already know the persecution of Assange is an assault on justice.

Great article Mr. Ritter. 😊